To order Audio Book directly, go to: https://www.audible.com/pd/B07H3C719D/

Historical Fiction with Ancestral Twist

(While working on my new book Cousins at War, I couldn’t help comparing the problems of 1861 with those confronting us today: polarity and political divides. From those thoughts came this fictional piece with characters you will meet in CAW.)

“Make way.” Marion Allender nudged his older brother Alex in an effort to secure a better view through the portal. “I can’t see. What’s she doin’?”

Alex was older according to the happenstance of birth, but both young men had been dead now for well over a century.

“Writing again,” Alex replied. “At least this time it’s with ink—on paper.”

“Not that queer machine?” queried Marion.

“Nah.”

“I’ve been thinkin’ on that, Alex. Even talked to some other fellas. She’s pressin’ on letters from the alphabet and it makes words appear on paper. I reckon it’s like the telegraph machine. Like that. Some new-fangled printing press.”

“She’s writing about us, brother. That’s what’s really odd. Why do ya think she is?”

Ruth tossed her notebook onto the porch table, took a swig of the now cold coffee, and sighed heavily. “This ain’t comin’, boys,” she said aloud. “If you can hear me, then guide me. How in tarnation (as you would say) does this scene play out?”

She shook her head in disbelief. Sometimes I think I’m mad, she thought. But yet . . . I know they’re here. Around. Some. How.

“I already led her to every document with my name on it,” growled Alex. “Ain’t no more I can do short of leaping down there and poofing in front of her.”

“I’d like to witness that—you poofing,” laughed Marion. “’Sides, how you know she’s not beseeching me for more information?”

“I’m honored that she wants to tell our story—me or you.”

“She is our cousin. I mean she woulda been if she lived when we did. Right?”

“Yeah, she’s descended from Aunt Jane. But it must be more than that.”

“Why more than that?” demanded Marion. “It’s a fair yarn to write, ‘bout two handsome brothers choosin’ different sides in the War of 1861.”

Alex looked at him hard. “There were other wars, other soldiers. She could have settled on any of them. Ones we knew about. Ones that came after we died. All shared our blood. Just like she shares it.”

“Pa always said you were a philosopher, Alex.”

“Marion, look down there. Look sharp. What do you see? Besides a Kentucky born old woman who keeps writing and writing?”

Marion gripped the sill of the portal, leaning out as far as possible in an effort to scan the world roiling below him. “It’s a golderned calamity, isn’t it?” he muttered.

“Exactly. I’ve been sittin’ here off and on for 147 years now. I’ve watched my country go through five or six wars, for God’s sake, since the one we fought in. I’ve seen riots, protests, unkindness, ungodliness of every stripe. What did we accomplish, Marion? What did I fight for? Why’d you even bother to take the oath of allegiance after comin’ home?”

“You think that’s why she wants to tell our story, Alex? Cause it might have some meaning still—down there?”

“I do, Marion. Short of poofin’ in and sending her to a premature grave, let’s help. Reenlist. Join the fight. Those people are so divided, so polarized. It reminds me too much of ‘61, ‘62, all that.”

“You may be right, Alex. She wants somebody to think on it. Think on what they’re doin’, what they’re sayin’. Just think on it.”

Ruth leaned over the porch railing. Her mind had wandered from the frustrating writing task to the lilting melodies of nearby songbirds—unseen but heard. So soothing, she thought. The slightest of breezes caressed her face, breaking her reverie. She brushed back whispery strands of gray hair and turned to gaze in its direction.

They are buried together in the Linden Grove, a cemetery in Covington, Kentucky. Union. Confederate. The boys of 1861 forever face one another across a grassy divide. Most are veterans of locally formed volunteer regiments: infantry, cavalry, mounted infantry. Kentucky is where South met North; or, as historian Bruce Catton wrote, where they “touched one another most intimately.” And Linden Grove is one of very few cemeteries in this nation which honors all of its boys who served their country. For all were true Sons of Kentucky.

From the 1850s well into the Reconstruction years, Kentucky was divided in its loyalties and politics, experiencing partisan strife and violence (sometimes under martial law). Most Sons of Kentucky served in the Union army. About 100,000 Kentuckians answered the call to arms for the Union cause—less than half that for the Confederacy. Recruiters had poured across the borders in an effort to solicit men for both sides. There were two governments and two governors in the state (commencing in late 1861), one duly elected to uphold the Constitution and the Union—the other a shadow government.

Covington, the site of Linden Grove, is arguably the northernmost city in the State of Kentucky. It sits directly across the Ohio River from Cincinnati. Prior to the Civil War there was not one bridge that spanned the river, but that hardly mattered. The river certainly did not provide a perfect border between North and South. Powerful cultural bonds grew between Southern Ohio and North Central Kentucky beginning with the time of pioneer settlement following the American Revolution. People routinely traveled from one side of the river to the other. It was a common occurrence that linked families and promoted growth and commerce.

Yet, Kentucky was never Ohio. Vast numbers of those men and women in flatboats were specifically setting out for the new State of Kentucky, their eyes set on lands bounding the Maysville Road (which ran from the river to Lexington). And where were they predominantly from? Virginia, and what is now West Virginia. Others came from Maryland, Pennsylvania and points north, of course. At about the same time of Ohio River migration settlers were pouring through the Cumberland Gap, in to the lands of southern and western Kentucky. Most of these folks were coming from deeper in the southern region of the country—few from the North.

By the time fifty or sixty years had passed, Kentucky was a state with undeniable bonds with the North but deep roots in the South. No wonder its sons were torn. It truly was a state that pitted brother against brother, and cousin against cousin. For example, the great statesman from Kentucky—Henry Clay—had three grandsons that wore Union blue and four who fought in Confederate gray.

In the book which I am currently researching, I weave the story of two sets of cousins from my ancestry who resided in North Central Kentucky. Three of the young men chose to enlist in various Union regiments, but the fourth would ride with the Kentucky 8th Cavalry (CSA), a regiment under the famed General John Hunt Morgan. These cousins and brothers literally faced off at Murfreesboro/Stones River and within their native state. It’s an amazing story with unimaginable suffering. The lead character of my current book, Jesse: 53rd Kentucky, was familiar with them all. Corporal Jesse J. Cook rests in the Linden Grove. I visited him and his comrades-in-arms (North and South) over Memorial Day weekend.

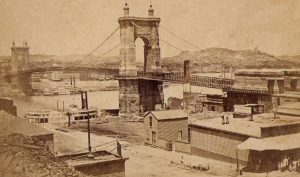

The iconic John A. Roebling Bridge has spanned the waters of the Ohio River between Covington and Cincinnati for over 150 years. It is a National Historic Landmark, still serving both pedestrian and vehicular traffic.

The first charter for the Covington-Cincinnati Bridge Company was granted by the Kentucky Legislature in 1846. (Kentucky owns the Ohio River—basically to the Ohio shoreline.) Due to intense opposition from ferryboat operators and steamboat companies, construction was delayed for ten years. There were also fears that a bridge would aid runaway slaves in reaching the North.

At the outbreak of the Civil War the towers on either side of the river were under construction. John Roebling had been hired early in the process to design the bridge. His son, Washington, was the engineer on site, who oversaw the construction and dealt with problems at hand. The project slowed during the first years of the war. Besides financial setbacks, both state legislatures had to approve lowering the required clearance of the bridge over the water. In 1863, work on the towers resumed, and continued through 1864. (This is when my character Pete Strong would have been employed on the crew.) Spinning of the cables began in November 1865 (meshing nicely with Jesse’s discharge from the army in September when he’s hoping to see construction of the bridge accelerate).

Jesse, Eliza, and the rest of the Cooks were surely among the 166,000 people from Kentucky and Ohio who crossed the bridge on its opening weekend in early December 1866. They no doubt marveled at the then longest bridge in the world—later to be surpassed by Roebling’s other bridge in Brooklyn.

Having grown up in Covington, I would hear of visitors saying, “Oh, doesn’t this look like the Brooklyn Bridge.” My reply, as a proud child of the Ohio River Valley, would inevitably be, “No, the Brooklyn Bridge looks like ours.”

(Adapted from: A Quick History of the Roebling Suspension Bridge/ Covington-Cincinnati Suspension Bridge Committee)